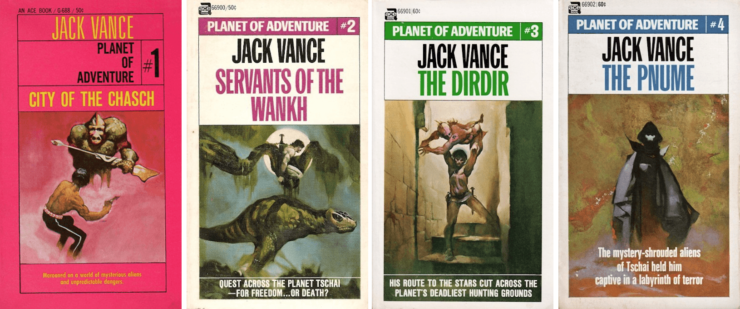

Author Jack Vance was such a driven world-creator that I’m beginning to suspect it was less of a talent and more of a compulsion. For a timely example of Vance’s relentless societal construction, take the Planet of Adventure quartet of novels, the middle two books of which are celebrating their fiftieth anniversary this year. The books have already been summarized quite well on this site, but I’ll give you the quick version: Space explorer Adam Reith arrives on the planet Tschai, and discovers that four alien races already call it home. The reptilian Chasch arrived thousands of years ago, followed by their enemies, the pantherlike Dirdir and the hulking amphibious Wankh. There’s also a mysterious race called the Pnume who are indigenous to Tschai. And there are humans—lots of them.

The Dirdir, it turns out, gathered up some neolithic humans when they visited earth tens of thousands of years ago, and have been breeding their descendants into a servant race. The Chasch and the Wankh have joined in, as have the Pnume, creating another quartet of exotic races: the Chaschmen, the Dirdirmen, the Wankhmen, and the Pnumekin. Then there are the various humans who live in the towns and wildernesses of Tsachi who have no alien affiliation, and who have created their own cultures in the shadows of the aliens’ cities.

If you’re keeping score, that’s over half a dozen distinct cultures; when you start reading the books, you soon find even more, as Reith encounters wildly varying societies of humans struggling to survive on the strange planet, some with elaborate customs and cities, others still operating at a caveman level.

Then there’s something else: In addition to the unified groups on Tschai, there are those who opt out of their groups—quite a few of them. The most dangerous are the Phung, a variety of Pnume that lose their minds and live like hermits, stealthily murdering whichever unwary individuals stumble through their territory. The humans are also capable of giving their societies the old heave-ho. Reith makes friends with two such trailblazers, Traz of the Emblem-Men, and Ankhe at afram Anacho, a ‘renegade’ Dirdirman who still, even though he’s basically now a free agent, regards the Dirdir race and ways as superior to all others, which must be problematic for him because the Dirdir occasionally hunt and eat humans.

It’s hard not to read all four books and reach a certain realization, maybe one that Vance intended: Culture is ridiculously arbitrary, whether you embrace it or rebel against it. The panorama of fictional societies presented in the books hammer home the baselessness of all forms of society, with their pointless ceremonies and deluded enterprises.

Yet leaving one’s culture means having to construct something in its place—a culture for one, and that’s insanity. Whenever he starts talking about his home civilization on Earth, Reith gets labeled a lunatic by the inhabitants of Tschai. The vast majority of humans and aliens would rather cling to the societies they inherited, rather than hang out with the Phung. Even Anacho can’t let go of his high opinion of the Dirdir.

This idea of sticking with your nation takes the Planet of Adventure quartet in an interesting direction, one that leads away from what people typically think of as “adventure.” While much of the books are set in the wilderness, especially the first two books, a great deal of the series is spent in port cities and fortified alien citadels where commerce and exchange take place. Reith proves time and again that he can survive very handily in the lawless wastelands, but he doesn’t spend any more time in them than he has to—especially not after he learns of the advanced countries and far-reaching shipping routes to be found on this new world. Overall, Reith seems to spend less time fighting to survive and more time putting together schemes to make money.

So while the title of the series and the Jeffrey Catherine Jones artwork adorning each paperback promise bare-knuckle conflict in a natural setting, Vance’s books develop into stories in which a ‘normal’ earthman repeatedly navigates culture-clashes with an endless string of civilized-in-their-own-way characters.

City of the Chasch has the least of this—there’s more travel in the wilderness, more small tribal groups, more ruined cities. The Chasch themselves seem to share the blasé attitude of the French Decadents—their civilization is repeatedly described as on the wane, and they seem to have trouble stirring themselves from their slide into irrelevance—making them akin to Earth’s castle-dwellers in Vance’s novella The Last Castle.

Buy the Book

Empress of Forever

Servants of the Wankh begins with Vance’s boldest statement yet on the civilization-madness connection. Having saved a young woman named Ylin Ylan, Reith and his entourage are escorting her back to her home nation of Cath, yet Reith learns that the Yao of Cath are a people very sensitive to shame. Their reaction to shameful setbacks is called awaile, which basically means going into a murderous rage and killing as many bystanders as one can before submitting to a public ritualized execution. Ylin Ylan, who was sent away from home to be a sacrifice of some sort, turns out to have a lot to be ashamed about, and she almost kills Reith and everyone else about the boat on which they’re traveling, before drowning herself. The whole event seems as arbitrary as it is unfortunate.

While Servants of the Wankh, with its mystery plot and evocative descriptions of Tschai’s rivers and the people inhabiting their banks, ends up being one of the best of the four books, The Dirdir is one of the most disappointing. Having spent chapters building up the Dirdir as a ferocious race descended from arboreal hunters—a people who continue to hunt in packs even though their civilization has advanced the point of interstellar travel—Vance dispatches the Dirdir a little too quickly, and Reith survives his encounters with them in the first part of the book not only without a scratch, but having acquired a fortune as well. Then the second half of the book involves Reith’s dealings with an unscrupulous businessman as he tries to build a spaceship that will take him home. Vance, who himself built boats and who probably had to deal with plenty of unscrupulous businessmen in the construction of such vessels, may be getting something personal off his chest, but it doesn’t make for a whole lot of adventure.

Which brings us to The Pnume, the final book in the quartet, a tale that almost dispenses entirely with the idea of wilderness. Captured by Tschai’s indigenous race, Reith comes to discover a vast network of tunnels and canals below the planet’s surface, and escaping the mysterious race ultimately involves no more than finding a reliable transit schedule, which he does. Tschai is not really a wild planet of mysterious expanses, because the Pnume have spent hundreds of thousands of years mapping every inch of it; Reith’s travels and battles across Tschai’s various landscapes were not so much a series of colorful brawls through uncharted territories as much as they were proscribed movements across a gameboard.

Reith’s efforts to get back to the warehouse where he built his spaceship contrast with the way the series opened, with Reith landing in the jungle and joining up with a paleolithic tribe. The ‘adventure’ of the series moves in the direction of civilization, complexity, and intricacy. That was Vance letting us into his inner sanctum and sharing the objects of his fascination with readers. If he was going to take us to a planet filled with people, he would make the trip more interesting with elaborations on what such people valued and believed—and he would do it dozens or even hundreds of times if he had to. While the old pulp definitions of ‘adventure’ focused on lone he-men picking up swords and ray-guns and hacking away at the collection of hazards they encountered in their strange new environments, Vance saw the possibilities for even greater adventure in the center of civilizations, and it sets his work apart. However far Adam Reith gets from the ports and market towns of Tschai, he always seems to circle back, returning to where the action is, and his moments of fisticuffs or life-and-death struggle occur throughout a landscape dotted with capitals and palaces, among hoteliers, con-men, clerics, and civic functionaries. Whatever beasts are lurking in Vance’s wilderness, he’s always got something more challenging waiting at the city gate.

Hector DeJean relives the pop-culture highlights of his misspent youth every day in his head. He’s written about television, superheroes, and TV superheroes for the Criminal Element.

To me, the most interesting facet of the book is Vance’s assertion that the fundamental humanity of even the most ‘alien’ of Tschai’s client races has survived. Reith remarks how even the dour Chaschmen seek out companionship in a tavern, and he muses that a surgically altered Dirdirman Immaculate partakes of the same original Earth substance that he himself does.

This is perhaps my favorite ‘planetary romance’, it is Jack Vance’s love letter to Barsoom.

That is a great aspect of his work, but my favorite Vance characteristic is his prose style. He was totally in control of that, too, because it was more florid in books where that was appropriate and more translucent in books where that was appropriate. He was a remarkable writer. Ironically, the next book I have lined up to read after I finish what I’m in the middle of is Hard Luck Diggings, the first in the 5 volume collection of early Vance stories. I’ve read some of them in other collections, but not all and it’s time that I did.

Thanks for this. I have a strong love of Tschai, as you know, since you liked to my own review of the quartet.

As far as the Dirdir, I thought Vance was trying to show Reith at perhaps his zenith as an action man on the planet. Ambushing Dirdir in the Carabas IS pretty audacious.

@Paul Weimer–I did indeed enjoy your Tschai essay very much. And maybe I’m being a little hard on The Dirdir–I just thought that the Dirdir were built up as this race of killers elite in earlier books, then when Reith and his crew get to the Carabas, they manage to kill an awful lot of those guys without too much difficulty (though the book does have a great moment of suspense, when Reith and his crew are racing for the border of the Carabas with several Dirdir hunting parties on their heels). But then the book spends too much time with Woudiver screwing over Reith, which made me impatient.

@@.-@. My take on the Dirdir is that they lacked any serious competition since the end of the Dirdir/Wankh wars, and that the hunters of the Carabas were totally unprepared for fighting an equally cunning, equally competent foe.

It’s as if a fox-hunting party of upper-class twits ended up facing a Siberian tiger instead of a fox.

The whole book is about how the aliens are overconfident- the Chasch are stagnant, the Wankh are naive, the Dirdir are atavistic, and the Pnume are obsessive. A Terran, equally technologically advanced, and full of the youthful vigor of space age humanity, is able to thwart them all, mainly because they never realize that he’s a threat.

Love the essay, love anything about Vance!